Diagnostic Testing of Influenza - CAM 134

Description

Influenza is an acute respiratory illness caused by influenza A or B viruses resulting in upper and lower respiratory tract infection, fever, malaise, headache, and weakness. It mainly occurs in outbreaks and epidemics during the winter season, and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in certain high-risk populations (Dolin, 2024b).

Rapid influenza diagnostic tests (RIDTs) refer to clinical laboratory improvement amendments (CLIA) waived immunoassays that can detect influenza viruses during the outpatient visit, giving results in a clinically relevant time period to inform treatment decisions (CDC, 2017). Besides RIDTs, influenza can be detected using polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assays as well as culture testing; however, the former is not often used in initial clinical management due to time constraints. Serologic testing is not used in outpatient settings for diagnosis (Dolin, 2024a).

Policy

Application of coverage criteria is dependent upon an individual’s benefit coverage at the time of the request.

- For symptomatic individuals (see Note 1), one (see Note 2), but not both, of the following is considered MEDICALLY NECESSARY:

- One single rapid flu test (either a point-of-care rapid nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) or a rapid antigen test).

- One single traditional NAAT.

- Viral culture testing for influenza in an outpatient setting is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- In asymptomatic patients, outpatient influenza testing, including rapid antigen flu tests, rapid NAAT or RT-PCR tests, traditional RT-PCR tests, and viral culture testing, is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY.

- Serology testing for influenza is considered NOT MEDICALLY NECESSARY under any circumstance.

Note 1: Typical Influenza Signs and Symptoms.3

- Fever or feeling feverish/chills

- Cough

- Sore throat

- Headaches

- Muscle or body aches

- Fatigue

- Runny or stuffy nose

- Vomiting and/or diarrhea (more common in children than adults)

Note 2: One influenza test may detect influenza A and/or influenza B. When both influenza A and influenza B are detected by a test represented by CPT codes 87400, 87501, or 87804, up to two units may be billed at a single visit.

Table of Terminology

| Term |

Definition |

| AAEM |

American Academy of Emergency Medicine |

| AAP |

American Academy of Paediatrics |

| ACOG | American College of obstetricians and Gynecologists |

| ATS |

American Thoracic Society |

| CDC |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CLIA |

Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments |

| DFA/IFA |

Direct or Indirect fluorescent antibody staining |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| EIA |

Enzyme immunoassay |

| ELISA |

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| FBC |

Full blood counts |

| FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

| FIA |

Fluorescence immunoassay |

| ICT |

Immunochromatographic |

| IDSA |

Infectious Diseases Society of America |

| IMCA |

Immunochemiluminometric assay |

| MDCK |

Madin-Darby Canine Kidney |

| NAAT |

Nucleic acid amplification test |

| NIBSC |

National Institute for Biological Standards and Control |

| NIH |

National Institute of Health |

| NPS |

Nasopharyngeal Swab |

| NPV |

Negative predictive value |

| PCR |

Polymerase chain reaction |

| POC |

Point-of-care |

| PPV |

Positive predictive value |

| RAD |

Rapid antigen diagnostic |

| RIDTs |

Rapid influenza diagnostic tests |

| RSV |

Respiratory syncytial virus |

| RT-PCR |

Reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction |

Rationale

The influenza virus causes seasonal epidemics that result in severe illnesses and death every year. Influenza characteristically begins with the abrupt onset of fever, headache, myalgia, and malaise,4-7 accompanied by manifestations of respiratory tract illness, such as nonproductive cough, sore throat, and nasal discharge.1

High titers of influenza virus are often present in respiratory secretions of infected persons. Influenza is transmitted primarily via respiratory droplets produced from sneezing and coughing which requires close contact with an infected individual.1,8,9 The typical incubation period for influenza is one to four days (average two days).2,10 The serial interval among household contacts is three to four days.11 When initiated promptly (within the first 24 to 30 hours), antiviral therapy can shorten the duration of influenza symptoms by approximately one-half to three days.12-18

In certain circumstances, the diagnosis of influenza can be made clinically, such as during an outbreak. At other times, it is important to establish the diagnosis using laboratory testing. Viral diagnostic test options include rapid antigen tests, immunofluorescence assays, and reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)-based testing.2 Among these, RT-PCR is the most sensitive and specific.1 Rapid influenza antigen tests are immunoassays that can identify influenza A and B viral nucleoprotein antigens in respiratory specimens which yield qualitative results in approximately 15 minutes or less.2 However, they have much lower sensitivity.2,19-21 A recent meta-analysis found that the sensitivity of these immunoassays was 62.3 percent, and the specificity was 98.2 percent.22 Furthermore, detectable viral shedding in respiratory secretions peaks at 24 to 48 hours of illness and then rapidly declines.1

A decision analysis by Sintchenko, et al. (2002) concluded that treatment based on rapid diagnostic testing results was appropriate first over empirical antiviral treatment, except during influenza epidemics. When the probability of a case being due to influenza reached 42 percent, the two strategies were equivalent. Further, a separate meta-analysis found that rapid diagnostic testing did not add to the overall cost-effectiveness of treatment if the probability of influenza was greater than 25 to 30 percent.1,24

Analytical Validity

Viral culture is a gold standard for influenza diagnosis, but it is very time-consuming with an average seven day turnaround time; on the other hand, real-time RT-PCR and shell vial (SV) testing require only an average of 4 hours and 48 hours, respectively. A study by Lopez Roa, et al. (2011) compared real-time RT-PCR and SV testing against conventional cell culture to detect pandemic influenza A H1N1. The sensitivity of real-time RT-PCR as compared to viral culture testing was 96.5%, and SV had a sensitivity of 73.3% and 65.1%, depending on the use of either A549 cells or Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) cells, respectively. The authors conclude, “Real-time RT-PCR displayed high sensitivity and specificity for the detection of influenza A H1N1 in adult patients when compared with conventional techniques.”25

Clinical Utility and Validity

Yoon, et al. (2017) investigated the use of saliva specimens for detecting influenza A and B using RIDTs. Both saliva and nasopharyngeal swab (NPS) samples were analyzed from 385 patients; each sample was assayed using four different RIDTs—the Sofia Influenza A+B Fluorescence Immunoassay, ichroma TRIAS Influenza A+B, SD Bioline Influenza Ag, and BinaxNOW Influenza A/B antigen kit—as well as real-time RT-PCR. Using real-time RT-PCR as a standard, 31.2% of the patients tested positive for influenza A and 7.5% for influenza B. All four RIDTS had “slightly higher” diagnostic sensitivity in NPS samples than saliva samples; however, both Sofia and ichroma “were significantly superior to those of the other conventional influenza RIDTs with both types of sample.”26 The authors note that the sensitivity of diagnosis improves if both saliva and NPS testing is performed (from 10% to 13% and from 10.3% to 17.2% for A and B, respectively). The researchers conclude, “this study demonstrates that saliva is a useful specimen for influenza detection, and that the combination of saliva and NPS could improve the sensitivities of influenza RIDTs.”26

Ryu, et al. (2016) investigated the efficacy of using instrument-based digital readout systems with RIDTs. In their 2016 paper, the authors included 314 NPS samples from patients with suspected influenza and tested each sample with the Sofia Influenza A+B Fluorescence Immunoassay and BD Veritor System Flu A+B, which use instrument-based digital readout systems, as well as the SD Bioline assay (a traditional immunochromatographic assay) and PCR, the standard. Relative to the RT-PCR standard, for influenza A, the sensitivities for the Sofia, BD Veritor, and SD Bioline assays were 74.2%, 73.0%, and 53.9%, respectively; likewise, for influenza B, the sensitivities, respectively, were 82.5%, 72.8%, and 71.0%. All RIDTS show 100% specificities for both subtypes A and B. The authors conclude, “Digital-based readout systems for the detection of the influenza virus can be applied for more sensitive diagnosis in clinical settings than conventional [RIDTs].”27 Similar research was performed in 2018 on NPS using RIDTs with digital readout systems—Sofia and Veritor as before along with BUDDI—as compared to standard RT-PCR and the SD Bioline immunochromatographic assay (n=218). The four RIDTs were also tested with diluted solutions from the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (NIBSC) to probe lower detection limits for each testing method. Again, the digital-based assays exhibited higher sensitivity for influenza. “Sofia showed the highest sensitivity for influenza A and B detection. BUDDI and Veritor showed higher detection sensitivity than a conventional RIDT for influenza A detection. Further study is needed to compare the test performance of RIDTs according to specific, prevalent influenza subtypes.”28

Another study compared the Alere iNAT, a rapid isothermal nucleic acid amplification assay, to the Sofia Influenza A+B and the BinaxNOW Influenza A&B immunochromatographic (ICT) assay. Using RT-PCR as the standard for 202 NPS samples, the “Alere iNAT detected 75% of those positive by RT-PCR, versus 33.3% and 25.0% for Sofia and BinaxNOW, respectively. The specificity of Alere iNAT was 100% for influenza A and 99% for influenza B.”29 BinaxNOW also had a sensitivity of only 69% for influenza as compared to RT-PCR in another study of 520 NPS from children under the age of five.30

Young, et al. (2017) investigated the accuracy of using point-of-care (POC) nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT)-based assays on NPS as compared to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-cleared in vitro PCR test, GenMark Dx Respiratory Viral Panel. Their study consisted of 87 NPS samples from adults. As compared to the RT-PCR gold standard, the cobas Liat Influenza A/B POC test had an overall sensitivity and specificity of 97.9% and 97.5%, respectively, whereas the Alere i Influenza A&B POC test’s sensitivity was only 63.8% with a specificity of 97.5%.31 Taken together, the authors conclude that “the cobas Influenza A/B assay demonstrated performance equivalent to laboratory-based PCR, and could replace rapid antigen tests.”31 These results are corroborated by another study that measured the specificity of the cobas POC assay as 100% for influenza A/B with a sensitivity of 96% for influenza A and 100% for influenza B.32 Further, a third study reported a 6.5% invalid rate (as defined by as a failure on a first-run assay) by the cobas POC assay; however, “the sensitivities and specificities for all assays [cobas, Xpert Xpress Flu/RSV, and Aries Flu A/B & RSV] were 96.0 to 100.0% and 99.3 to 100% for all three viruses [influenza A, influenza B, and respiratory syncytial virus].”33

Antoniol, et al. (2018) aimed to evaluate the usage of rapid influenza diagnostic tests (RIDTs) in adults, particularly the OSOM® Ultra Flu A&B on viral strains of influenza A/B in the emergency department. The diagnostic evaluation of this test was compared against the Xpert® Flu PCR test. The PCR test had a sensitivity of 98.4%, specificity of 99.7%, positive predictive value (PPV) of 99.2% and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 99.5%, whereas the OSOM® Ultra Flu A&B RIDT had a sensitivity of 95.1%, specificity of 98.4%, positive predictive value of 95.1%, and negative predictive value of 98.4%. However, “there was no difference in test performance between influenza A and B virus nor between the influenza A subtypes,” thereby solidifying the use of both the PCR and RIDT in diagnosing influenza strains in adult and elderly patients.34

Lee, et al. (2019) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis on point-of-care tests (POCTs) for influenza in ambulatory care settings. After screening, seven randomized studies and six non-randomized studies from studies mostly from pediatric emergency departments were included. The researchers concluded that “in randomized trials, POCTs had no effect on admissions (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.61-1.42, I2 = 34%), returning for care (RR 1.00 95% CI = 0.77-1.29, I2 = 7%), or antibiotic prescribing (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.82-1.15, I2 = 70%), but increased prescribing of antivirals (RR 2.65, 95% CI 1.95-3.60; I2 = 0%). Further testing was reduced for full blood counts (FBC) (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.69-0.92 I2 = 0%), blood cultures (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.68-0.99; I2 = 0%) and chest radiography (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.68-0.96; I2 = 32%), but not urinalysis (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.78-w1.07; I2 = 20%).” Among the non-randomized studies, fewer reported these outcomes, with some showing inconsistency with the randomized trial outcomes, such as there being fewer antibiotic prescriptions and less urinalysis testing. This demonstrated the use of POCTs for influenza and how they influence clinical treatment and decision making.35

Kanwar, et al. (2020) compared three rapid, POC molecular assays for influenza A and B detection in children: the ID Now influenza A & B assay, the Cobas influenza A/B NAAT, and Xpert Xpress Flu. Each of the three aforementioned tests are CLIA-waived influenza assays. PCR was used to compare results from each. NPS Samples from 201 children were analyzed for this study. The researchers note that “The overall sensitivities for the ID Now assay, LIAT, and Xpert assay for Flu A virus detection (93.2%, 100%, and 100%, respectively) and Flu B virus detection (97.2%, 94.4%, and 91.7%, respectively) were comparable. The specificity for Flu A and B virus detection by all methods was >97%.”36

Sato, et al. (2022) conducted a study comparing the results from rapid antigen detection (Quick Chaser Flu A, B), silver amplified immunochromatography (Quick Chaser Auto Flu A, B), and two separate NAATs (Xpert Xpress Flu/RSV and cobas Influenza A/B & RSV). The researchers also used a baseline RT-PCR assay as a reference for the study results. The sensitivities of the rapid antigen detection test and silver amplified immunochromatography test were 41.7% and 50.0% <6 hours after onset, but both were 100% in sensitivity at 24-48h after onset. Ultimately, the researchers concluded that the two NAATs had comparable analytical performances, whereas the rapid antigen detection and silver amplified immunochromatography tests had increased false negatives oftentimes when viral load is low in early infection.37

Ferrani, et al. (2023) studied the performance of a rapid antigen diagnostic testing in children with respiratory infections. The study included 236 children with clinical signs and symptoms of SARS-CoV-2, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and influenza. The children were tested with the rapid antigen diagnostic test “COVID-VIRO ALL IN TRIPLEX” using a self-collected anterior nasal swab. The children were also tested with a multiplex RT-PCR for comparison. The sensitivity of the rapid antigen diagnostic test was 88.9% for SARS-Cov-2, 79.1% for RSV, and 91.6% for influenza. The specificity for the rapid antigen diagnostic test was 100% for SARS-CoV-2, RSV, and influenza. The authors conclude that “this easy-to-perform triplex test is a considerable advance, allowing clinicians to obtain an accurate diagnosis in most cases of respiratory infection” but note that “more data are needed to validate this test in different contexts and across several seasons.”38

Another study compared the Alere iNAT, a rapid isothermal nucleic acid amplification assay, to the Sofia Influenza A+B and the BinaxNOW Influenza A&B immunochromatographic (ICT) assay. Using RT-PCR as the standard for 202 NPS samples, the “Alere iNAT detected 75% of those positive by RT-PCR, versus 33.3% and 25.0% for Sofia and BinaxNOW, respectively. The specificity of Alere iNAT was 100% for influenza A and 99% for influenza B.”29 BinaxNOW also had a sensitivity of only 69% for influenza as compared to RT-PCR in another study of 520 NPS from children under the age of five.30

Young, et al. (2017) investigated the accuracy of using point-of-care (POC) nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT)-based assays on NPS as compared to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-cleared in vitro PCR test, GenMark Dx Respiratory Viral Panel. Their study consisted of 87 NPS samples from adults. As compared to the RT-PCR gold standard, the cobas Liat Influenza A/B POC test had an overall sensitivity and specificity of 97.9% and 97.5%, respectively, whereas the Alere i Influenza A&B POC test’s sensitivity was only 63.8% with a specificity of 97.5%.31 Taken together, the authors conclude that “the cobas Influenza A/B assay demonstrated performance equivalent to laboratory-based PCR, and could replace rapid antigen tests.”31 These results are corroborated by another study that measured the specificity of the cobas POC assay as 100% for influenza A/B with a sensitivity of 96% for influenza A and 100% for influenza B.32 Further, a third study reported a 6.5% invalid rate (as defined by as a failure on a first-run assay) by the cobas POC assay; however, “the sensitivities and specificities for all assays [cobas, Xpert Xpress Flu/RSV, and Aries Flu A/B & RSV] were 96.0 to 100.0% and 99.3 to 100% for all three viruses [influenza A, influenza B, and respiratory syncytial virus].”33

Antoniol, et al. (2018) aimed to evaluate the usage of rapid influenza diagnostic tests (RIDTs) in adults, particularly the OSOM® Ultra Flu A&B on viral strains of influenza A/B in the emergency department. The diagnostic evaluation of this test was compared against the Xpert® Flu PCR test. The PCR test had a sensitivity of 98.4%, specificity of 99.7%, positive predictive value (PPV) of 99.2% and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 99.5%, whereas the OSOM® Ultra Flu A&B RIDT had a sensitivity of 95.1%, specificity of 98.4%, positive predictive value of 95.1%, and negative predictive value of 98.4%. However, “there was no difference in test performance between influenza A and B virus nor between the influenza A subtypes,” thereby solidifying the use of both the PCR and RIDT in diagnosing influenza strains in adult and elderly patients.34

Lee, et al. (2019) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis on point-of-care tests (POCTs) for influenza in ambulatory care settings. After screening, seven randomized studies and six non-randomized studies from studies mostly from pediatric emergency departments were included. The researchers concluded that “in randomized trials, POCTs had no effect on admissions (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.61-1.42, I2 = 34%), returning for care (RR 1.00 95% CI = 0.77-1.29, I2 = 7%), or antibiotic prescribing (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.82-1.15, I2 = 70%), but increased prescribing of antivirals (RR 2.65, 95% CI 1.95-3.60; I2 = 0%). Further testing was reduced for full blood counts (FBC) (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.69-0.92 I2 = 0%), blood cultures (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.68-0.99; I2 = 0%) and chest radiography (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.68-0.96; I2 = 32%), but not urinalysis (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.78-w1.07; I2 = 20%).” Among the non-randomized studies, fewer reported these outcomes, with some showing inconsistency with the randomized trial outcomes, such as there being fewer antibiotic prescriptions and less urinalysis testing. This demonstrated the use of POCTs for influenza and how they influence clinical treatment and decision making.35

Kanwar, et al. (2020) compared three rapid, POC molecular assays for influenza A and B detection in children: the ID Now influenza A & B assay, the Cobas influenza A/B NAAT, and Xpert Xpress Flu. Each of the three aforementioned tests are CLIA-waived influenza assays. PCR was used to compare results from each. NPS Samples from 201 children were analyzed for this study. The researchers note that “The overall sensitivities for the ID Now assay, LIAT, and Xpert assay for Flu A virus detection (93.2%, 100%, and 100%, respectively) and Flu B virus detection (97.2%, 94.4%, and 91.7%, respectively) were comparable. The specificity for Flu A and B virus detection by all methods was >97%.”36

Sato, et al. (2022) conducted a study comparing the results from rapid antigen detection (Quick Chaser Flu A, B), silver amplified immunochromatography (Quick Chaser Auto Flu A, B), and two separate NAATs (Xpert Xpress Flu/RSV and cobas Influenza A/B & RSV). The researchers also used a baseline RT-PCR assay as a reference for the study results. The sensitivities of the rapid antigen detection test and silver amplified immunochromatography test were 41.7% and 50.0% <6 hours after onset, but both were 100% in sensitivity at 24-48h after onset. Ultimately, the researchers concluded that the two NAATs had comparable analytical performances, whereas the rapid antigen detection and silver amplified immunochromatography tests had increased false negatives oftentimes when viral load is low in early infection.37

Ferrani, et al. (2023) studied the performance of a rapid antigen diagnostic testing in children with respiratory infections. The study included 236 children with clinical signs and symptoms of SARS-CoV-2, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and influenza. The children were tested with the rapid antigen diagnostic test “COVID-VIRO ALL IN TRIPLEX” using a self-collected anterior nasal swab. The children were also tested with a multiplex RT-PCR for comparison. The sensitivity of the rapid antigen diagnostic test was 88.9% for SARS-Cov-2, 79.1% for RSV, and 91.6% for influenza. The specificity for the rapid antigen diagnostic test was 100% for SARS-CoV-2, RSV, and influenza. The authors conclude that “this easy-to-perform triplex test is a considerable advance, allowing clinicians to obtain an accurate diagnosis in most cases of respiratory infection” but note that “more data are needed to validate this test in different contexts and across several seasons.”38

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

The CDC gives two sets of guidelines concerning testing for influenza. If influenza is known to be circulating in the community, they give the algorithm displayed in the figure below:39

If the patient is asymptomatic for influenza, then they do not recommend testing. If the patient is symptomatic and is being admitted to the hospital, then they recommend testing; on the other hand, if a symptomatic patient is not being admitted to the hospital, they recommend testing if the results of the test will influence clinical management. Otherwise, if the test results are not going to influence the clinical management, then do not test but do administer empiric antiviral treatment for any patient in high-risk categories.39

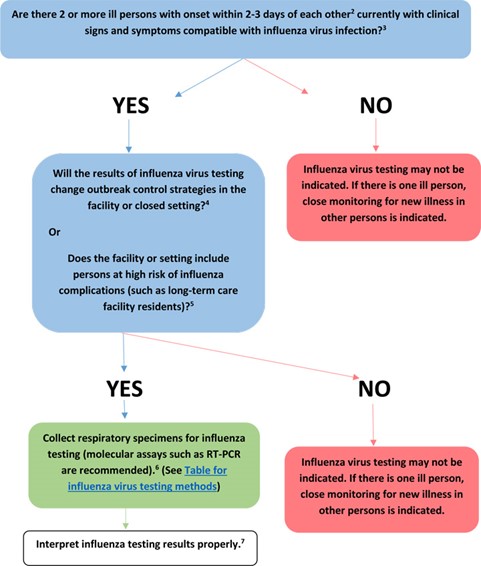

For possible outbreaks in a closed setting or institution, the CDC issued the guideline algorithm in the figure below:40

If only one person is showing signs and symptoms of influenza, then testing is not recommended but he/she should be closely monitored. If multiple people are showing signs of influenza, then RT-PCR testing is recommended if the results would change control strategies or if there are persons at high risk of complications within the facility or closed setting.40

The CDC notes the usefulness of RIDT influenza testing given the rapid testing time (less than 15 minutes on average) and that some have been cleared for point-of-care use, but they note the limited sensitivity to detect influenza as compared to the reference standards for laboratory confirmation testing, RT-PCR, or viral culture. Disadvantages of RIDTs include high false negative results, especially during outbreaks, false positive results during times when influenza activity is low, and the lack of parity in RIDTs in detecting viral antigens. “Testing is not needed for all patients with signs and symptoms of influenza to make antiviral treatment decisions. Once influenza activity has been documented in the community or geographic area, a clinical diagnosis of influenza can be made for outpatients with signs and symptoms consistent with suspected influenza, especially during periods of peak influenza activity in the community.”2

The CDC notes the practicality of using RIDTs to detect possible influenza outbreaks, especially in closed settings. “RIDTs can be useful to identify influenza virus infection as a cause of respiratory outbreaks in any setting, but especially in institutions (i.e., nursing homes, chronic care facilities, and hospitals), cruise ships, summer camps, schools, etc. Positive RIDT results from one or more ill persons with suspected influenza can support decisions to promptly implement infection prevention and control measures for influenza outbreaks. However, negative RIDT results do not exclude influenza virus infection as a cause of a respiratory outbreak because of the limited sensitivity of these tests. Testing respiratory specimens from several persons with suspected influenza will increase the likelihood of detecting influenza virus infection if influenza virus is the cause of the outbreak, and use of molecular assays such as RT-PCR is recommended if the cause of the outbreak is not determined and influenza is suspected. Public health authorities should be notified promptly of any suspected institutional outbreak and respiratory specimens should be collected from ill persons (whether positive or negative by RIDT) and sent to a public health laboratory for more accurate influenza testing by molecular assays and viral culture.” The CDC recommends using a molecular assay, such as RT-PCR, to test any hospitalized individual with suspected influenza rather than using an RIDT.2

Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)

The IDSA published an update to seasonal influenza in adults and children in 2018. Here, IDSA propounded the following patient populations as targets for influenza testing:

“Outpatients (Including Emergency Department Patients)

- During influenza activity (defined as the circulation of seasonal influenza A and B viruses among persons in the local community) . . .:

- Clinicians should test for influenza in high-risk patients, including immunocompromised persons who present with influenza-like illness, pneumonia, or nonspecific respiratory illness (e.g., cough without fever) if the testing result will influence clinical management (A–III).

- Clinicians should test for influenza in patients who present with acute onset of respiratory symptoms with or without fever, and either exacerbation of chronic medical conditions (e.g., asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], heart failure) or known complications of influenza (e.g., pneumonia) if the testing result will influence clinical management (A-III).

- Clinicians can consider influenza testing for patients not at high risk for influenza complications who present with influenza-like illness, pneumonia, or nonspecific respiratory illness (e.g., cough without fever) and who are likely to be discharged home if the results might influence antiviral treatment decisions or reduce use of unnecessary antibiotics, further diagnostic testing, and time in the emergency department, or if the results might influence antiviral treatment or chemoprophylaxis decisions for high-risk household contacts . . . (C-III).

- During low influenza activity without any link to an influenza outbreak:

- Clinicians can consider influenza testing in patients with acute onset of respiratory symptoms with or without fever, especially for immunocompromised and high-risk patients (B-III).

Hospitalized Patients

- During influenza activity:

- Clinicians should test for influenza on admission in all patients requiring hospitalization with acute respiratory illness, including pneumonia, with or without fever (A-II).

- Clinicians should test for influenza on admission in all patients with acute worsening of chronic cardiopulmonary disease (e.g., COPD, asthma, coronary artery disease, or heart failure), as influenza can be associated with exacerbation of underlying conditions (A-III).

- Clinicians should test for influenza on admission in all patients who are immunocompromised or at high risk of complications and present with acute onset of respiratory symptoms with or without fever, as the manifestations of influenza in such patients are frequently less characteristic than in immunocompetent individuals (A-III).

- Clinicians should test for influenza in all patients who, while hospitalized, develop acute onset of respiratory symptoms, with or without fever, or respiratory distress, without a clear alternative diagnosis (A-III).

- During periods of low influenza activity:

- Clinicians should test for influenza on admission in all patients requiring hospitalization with acute respiratory illness, with or without fever, who have an epidemiological link to a person diagnosed with influenza, an influenza outbreak or outbreak of acute febrile respiratory illness of uncertain cause, or who recently traveled from an area with known influenza activity (A-II).

- Clinicians can consider testing for influenza in patients with acute, febrile respiratory tract illness, especially children and adults who are immunocompromised or at high risk of complications, or if the results might influence antiviral treatment or chemoprophylaxis decisions for high-risk household contacts . . . (B-III).”41

The following three recommendations relating to the type of outpatient influenza testing were published also included:

- “Clinicians should use rapid molecular assays (i.e., nucleic acid amplification tests) over rapid influenza diagnostic tests (RIDTs) in outpatients to improve detection of influenza virus infection.”

- “Clinicians should not use viral culture for initial or primary diagnosis of influenza because results will not be available in a timely manner to inform clinical management (A-III), but viral culture can be considered to confirm negative test results from RIDTs and immunofluorescence assays, such as during an institutional outbreak, and to provide isolates for further characterization.”

- “Clinicians should not use serologic testing for diagnosis of influenza because results from a single serum specimen cannot be reliably interpreted, and collection of paired (acute/convalescent) sera 2–3 weeks apart are needed for serological testing.”41

The 2024 IDSA guidelines for the diagnosis of infectious diseases by microbiology laboratories under viral pneumonia respiratory infections, specifically including influenza, state: “Rapid antigen tests for respiratory virus detection lack sensitivity and depending upon the product, specificity. A meta-analysis of rapid influenza antigen tests showed a pooled sensitivity of 62.3% and a pooled specificity of 98.2%. They should be considered as screening tests only. At a minimum, a negative result should be verified by another method… Several US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-cleared NAAT platforms are currently available and vary in their approved specimen requirements and range of analytes detected.”42 Moreover, they state that the “IDSA/American Thoracic Society21 practice guidelines (currently under revision) consider diagnostic testing as optional for the patient who is not hospitalized.” For children, though, they do recommend testing for viral pathogens in both outpatient and inpatient settings. In the section on general influenza virus infection, again they recommend the use of rapid testing assays, noting the higher sensitivity of the NAAT-based methods over the rapid antigen detection assays. They also state: Serologic testing is not useful for the routine diagnosis of influenza due to high rates of vaccination and/or prior exposure.”43

American Academy of Emergency Medicine (AAEM)

The AAEM approved a clinical practice paper on influenza in the emergency department: vaccination, diagnosis, and treatment. This document provides a “Level B” recommendation, stating “Testing for influenza should only be performed if the results will change clinical management. If a RAD [rapid antigen diagnostic] testing method is utilized, the provider should be aware of the limited sensitivity and the potential for false negatives. If clinical suspicion is moderate to high and RAD test is negative, one should consider sending a confirmatory RT-PCR or proceeding with empiric treatment for suspected influenza.”44 This guideline has since been archived on the AAEM website.

Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), 32nd Edition (2021-2024, Red Book)

The Committee on Infectious Diseases released joint guidelines with the American Academy of Pediatrics. These joint guidelines recommend that “influenza testing should be performed when the results are anticipated to influence clinical management (e.g., to inform the decision to initiate antiviral therapy or antibiotic agents, to pursue other diagnostic testing or to implement infection prevention and control measures).”45

Regarding types of testing, the AAP states that “The decision to test is related to the level local influenza activity, clinical suspicion for influenza, and the sensitivity and specificity of commercially available influenza tests… These include rapid molecular assays for influenza RNA or nucleic acid detection, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) single-plex or multiplex assays, real time or other RNA-based assays, immunofluorescence assays (direct [DFA] or indirect [IFA] fluorescent antibody staining) for antigen detection, rapid influenza diagnostic tests (RIDTs) based on antigen detection, rapid cell culture (shell vial culture), and viral tissue cell culture (conventional) for virus isolation. The optimal choice of influenza test depends on the clinical setting.”45

The AAP recommendations for prevention and control of influenza in children recommend:46

- “Influenza testing should be performed in children with signs and symptoms of influenza when test results are anticipated to impact clinical management (e.g., to inform the decision to initiate antiviral therapy, pursue other diagnostic testing, initiate infection prevention and control measures, or distinguish from other respiratory viruses with similar symptoms [e.g., severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2]).

- When influenza is circulating in the community, hospitalized patients with signs and symptoms of influenza should be tested with a molecular assay with high sensitivity and specificity (e.g., reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction).

- At-home tests are available for children as young as 2 years of age but data on the use of these tests in pediatric patients is limited. The use of at-home test results to inform treatment decisions should be informed by the sensitivity and specificity of the test, the prevalence of influenza in the community, the presence and duration of compatible signs and symptoms, and individual risk factors and comorbidities.”

National Institute of Health (NIH)

The NIH published a webpage on influenza diagnoses. This page notes that “Diagnostics that enable healthcare professionals to quickly distinguish one flu strain from another at the point of patient care and to detect resistance to antiviral drugs would ensure that patients receive the most appropriate care.”47

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)

The ACOG recommends that “when testing is available, pregnant individuals presenting with symptoms of respiratory illness should be tested for both influenza and SARS-CoV-2 infection” but “antiviral treatment should not be delayed while awaiting respiratory infection test results, and a patient's vaccination status should not affect the decision to treat.”48

References

- Dolin R. Seasonal influenza in adults: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis. Updated April 2, 2025. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/seasonal-influenza-in-adults-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis

- CDC. Rapid Influenza Diagnostic Tests. Updated September 17, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/hcp/testing-methods/clinician_guidance_ridt.html

- CDC. Signs and Symptoms of Flu. Updated August 24, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/signs-symptoms/index.html

- Dolin R. Influenza: current concepts. American family physician. 1976;14(3):72-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/961563/

- Loeb M, Singh PK, Fox J, et al. Longitudinal study of influenza molecular viral shedding in Hutterite communities. The Journal of infectious diseases. Oct 01 2012;206(7):1078-84. doi:10.1093/infdis/jis450

- Kilbourne ED, Loge JP. Influenza A prime: a clinical study of an epidemic caused by a new strain of virus. Annals of internal medicine. Aug 1950;33(2):371-9. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-33-2-371

- Nicholson KG. Clinical features of influenza. Seminars in respiratory infections. 1992;7(1):26-37. Accessed Mar. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1609165/

- Brankston G, Gitterman L, Hirji Z, Lemieux C, Gardam M. Transmission of influenza A in human beings. The Lancet Infectious diseases. Apr 2007;7(4):257-65. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(07)70029-4

- Mubareka S, Lowen AC, Steel J, Coates AL, Garcia-Sastre A, Palese P. Transmission of influenza virus via aerosols and fomites in the guinea pig model. The Journal of infectious diseases. Mar 15 2009;199(6):858-65. doi:10.1086/597073

- Cox NJ, Subbarao K. Influenza. Lancet (London, England). Oct 09 1999;354(9186):1277-82. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(99)01241-6

- Cowling BJ, Chan KH, Fang VJ, et al. Comparative epidemiology of pandemic and seasonal influenza A in households. The New England journal of medicine. Jun 10 2010;362(23):2175-84. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0911530

- Zachary KC. Seasonal influenza in nonpregnant adults: Treatment. Updated May 6, 2025. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/seasonal-influenza-in-nonpregnant-adults-treatment

- Cooper NJ, Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, Wailoo A, Turner D, Nicholson KG. Effectiveness of neuraminidase inhibitors in treatment and prevention of influenza A and B: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed). Jun 07 2003;326(7401):1235. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7401.1235

- Hayden FG, Osterhaus AD, Treanor JJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of the neuraminidase inhibitor zanamivir in the treatment of influenzavirus infections. GG167 Influenza Study Group. The New England journal of medicine. Sep 25 1997;337(13):874-80. doi:10.1056/nejm199709253371302

- Nicholson KG, Aoki FY, Osterhaus AD, et al. Efficacy and safety of oseltamivir in treatment of acute influenza: a randomised controlled trial. Neuraminidase Inhibitor Flu Treatment Investigator Group. Lancet (London, England). May 27 2000;355(9218):1845-50. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02288-1

- Dobson J, Whitley RJ, Pocock S, Monto AS. Oseltamivir treatment for influenza in adults: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet (London, England). May 02 2015;385(9979):1729-37. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(14)62449-1

- Heneghan CJ, Onakpoya I, Thompson M, Spencer EA, Jones M, Jefferson T. Zanamivir for influenza in adults and children: systematic review of clinical study reports and summary of regulatory comments. BMJ (Clinical research ed). Apr 09 2014;348:g2547. doi:10.1136/bmj.g2547

- Jefferson T, Jones M, Doshi P, Spencer EA, Onakpoya I, Heneghan CJ. Oseltamivir for influenza in adults and children: systematic review of clinical study reports and summary of regulatory comments. BMJ (Clinical research ed). Apr 09 2014;348:g2545. doi:10.1136/bmj.g2545

- Harper SA, Bradley JS, Englund JA, et al. Seasonal influenza in adults and children--diagnosis, treatment, chemoprophylaxis, and institutional outbreak management: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Apr 15 2009;48(8):1003-32. doi:10.1086/598513

- Hurt AC, Alexander R, Hibbert J, Deed N, Barr IG. Performance of six influenza rapid tests in detecting human influenza in clinical specimens. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. Jun 2007;39(2):132-5. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2007.03.002

- Ikenaga M, Kosowska-Shick K, Gotoh K, et al. Genotypes of macrolide-resistant pneumococci from children in southwestern Japan: raised incidence of strains that have both erm(B) and mef(A) with serotype 6B clones. Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease. Sep 2008;62(1):16-22. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.10.013

- Chartrand C, Leeflang MM, Minion J, Brewer T, Pai M. Accuracy of rapid influenza diagnostic tests: a meta-analysis. Annals of internal medicine. Apr 03 2012;156(7):500-11. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-156-7-201204030-00403

- Sintchenko V, Gilbert GL, Coiera E, Dwyer D. Treat or test first? Decision analysis of empirical antiviral treatment of influenza virus infection versus treatment based on rapid test results. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. Jul 2002;25(1):15-21. doi:10.1016/s1386-6532(00)00182-7

- Call SA, Vollenweider MA, Hornung CA, Simel DL, McKinney WP. Does this patient have influenza? Jama. Feb 23 2005;293(8):987-97. doi:10.1001/jama.293.8.987

- Lopez Roa P, Catalan P, Giannella M, Garcia de Viedma D, Sandonis V, Bouza E. Comparison of real-time RT-PCR, shell vial culture, and conventional cell culture for the detection of the pandemic influenza A (H1N1) in hospitalized patients. Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease. Apr 2011;69(4):428-31. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.11.007

- Yoon J, Yun SG, Nam J, Choi SH, Lim CS. The use of saliva specimens for detection of influenza A and B viruses by rapid influenza diagnostic tests. Journal of virological methods. May 2017;243:15-19. doi:10.1016/j.jviromet.2017.01.013

- Ryu SW, Lee JH, Kim J, et al. Comparison of two new generation influenza rapid diagnostic tests with instrument-based digital readout systems for influenza virus detection. British journal of biomedical science. Jul 2016;73(3):115-120. doi:10.1080/09674845.2016.1189026

- Ryu SW, Suh IB, Ryu SM, et al. Comparison of three rapid influenza diagnostic tests with digital readout systems and one conventional rapid influenza diagnostic test. Journal of clinical laboratory analysis. Feb 2018;32(2)doi:10.1002/jcla.22234

- Hazelton B, Gray T, Ho J, Ratnamohan VM, Dwyer DE, Kok J. Detection of influenza A and B with the Alere i Influenza A & B: a novel isothermal nucleic acid amplification assay. Influenza and other respiratory viruses. May 2015;9(3):151-4. doi:10.1111/irv.12303

- Moesker FM, van Kampen JJA, Aron G, et al. Diagnostic performance of influenza viruses and RSV rapid antigen detection tests in children in tertiary care. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. Jun 2016;79:12-17. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2016.03.022

- Young S, Illescas P, Nicasio J, Sickler JJ. Diagnostic accuracy of the real-time PCR cobas((R)) Liat((R)) Influenza A/B assay and the Alere i Influenza A&B NEAR isothermal nucleic acid amplification assay for the detection of influenza using adult nasopharyngeal specimens. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. Sep 2017;94:86-90. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2017.07.012

- Melchers WJG, Kuijpers J, Sickler JJ, Rahamat-Langendoen J. Lab-in-a-tube: Real-time molecular point-of-care diagnostics for influenza A and B using the cobas(R) Liat(R) system. Journal of medical virology. Aug 2017;89(8):1382-1386. doi:10.1002/jmv.24796

- Ling L, Kaplan SE, Lopez JC, Stiles J, Lu X, Tang YW. Parallel Validation of Three Molecular Devices for Simultaneous Detection and Identification of Influenza A and B and Respiratory Syncytial Viruses. Journal of clinical microbiology. Mar 2018;56(3)doi:10.1128/jcm.01691-17

- Antoniol S, Fidouh N, Ghazali A, et al. Diagnostic performances of the Xpert(®) Flu PCR test and the OSOM(®) immunochromatographic rapid test for influenza A and B virus among adult patients in the Emergency Department. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. Feb-Mar 2018;99-100:5-9. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2017.12.005

- Lee JJ, Verbakel JY, Goyder CR, et al. The Clinical Utility of Point-of-Care Tests for Influenza in Ambulatory Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Jun 18 2019;69(1):24-33. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy837

- Kanwar N, Michael J, Doran K, Montgomery E, Selvarangan R. Comparison of the ID Now Influenza A & B 2, Cobas Influenza A/B, and Xpert Xpress Flu Point-of-Care Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests for Influenza A/B Virus Detection in Children. Journal of clinical microbiology. Feb 24 2020;58(3)doi:10.1128/jcm.01611-19

- Sato Y, Nirasawa S, Saeki M, et al. Comparative study of rapid antigen testing and two nucleic acid amplification tests for influenza virus detection. J Infect Chemother. Jul 2022;28(7):1033-1036. doi:10.1016/j.jiac.2022.04.009

- Ferrani S, Prazuck T, Béchet S, Lesne F, Cohen R, Levy C. Diagnostic accuracy of a rapid antigen triple test (SARS-CoV-2, respiratory syncytial virus, and influenza) using anterior nasal swabs versus multiplex RT-PCR in children in an emergency department. Infect Dis Now. Oct 2023;53(7):104769. doi:10.1016/j.idnow.

2023.104769 - CDC. Guide for considering influenza testing when influenza viruses are circulating in the community. Updated November 24, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/hcp/testing-methods/consider-influenza-testing.html

- CDC. Influenza virus testing in investigational outbreaks in institutional or other closed settings. Updated March 4, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/hcp/testing-methods/guide-virus-diagnostic-tests.html

- Uyeki TM, Bernstein HH, Bradley JS, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America: 2018 Update on Diagnosis, Treatment, Chemoprophylaxis, and Institutional Outbreak Management of Seasonal Influenzaa. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2018;68(6):e1-e47. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy866

- Miller JM, Binnicker MJ, Campbell S, et al. A Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2018 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiologya. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2018:ciy381-ciy381. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy381

- Miller JM, Binnicker MJ, Campbell S, et al. Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2024 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society for Microbiology (ASM). Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Mar 5 2024;doi:10.1093/cid/ciae104

- Abraham MK, Perkins J, Vilke GM, Coyne CJ. Influenza in the Emergency Department: Vaccination, Diagnosis, and Treatment: Clinical Practice Paper Approved by American Academy of Emergency Medicine Clinical Guidelines Committee. The Journal of emergency medicine. Mar 2016;50(3):536-42. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.10.013

- AAP. Red Book® 2024-2027: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 33rd Edition. 2024;doi:10.1542/9781610027373

- Committee On Infectious Diseases. Recommendations for Prevention and Control of Influenza in Children, 2023-2024. Pediatrics. Oct 1 2023;152(4)doi:10.1542/peds.

2023-063772 - NIH. Influenza Diagnosis. Updated April 10, 2017. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/diseases-conditions/influenza-diagnosis

- ACOG. Influenza in Pregnancy: Prevention and Treatment. Updated February 2024. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-statement/articles/2024/02/influenza-in-pregnancy-prevention-and-treatment

- Kux L. Microbiology Devices; Reclassification of Influenza Virus Antigen Detection Test Systems Intended for Use Directly With Clinical Specimens. Federal Register; 2017;82(8):3609-19. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2017-01-12/pdf/2017-00199.pdf

- Azar MM, Landry ML. Detection of Influenza A and B Viruses and Respiratory Syncytial Virus by Use of Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA)-Waived Point-of-Care Assays: a Paradigm Shift to Molecular Tests. Journal of clinical microbiology. Jul 2018;56(7)doi:10.1128/jcm.00367-18

- CMS. Tests Granted Waived Status Under CLIA. https://www.cdc.gov/clia/docs/tests-granted-waived-status-under-clia.pdf

Coding Section

| CODE |

NUMBER |

DESCRIPTION |

| CPT |

86710 |

Antibody; influenza virus |

|

|

87254 |

Virus isolation; centrifuge enhanced (shell vial) technique, includes identification with immunofluorescence stain, each virus |

|

|

87275 |

Infectious agent antigen detection by immunofluorescent technique; influenza B virus |

|

|

87276 |

Infectious agent antigen detection by immunofluorescent technique; influenza A virus |

|

|

87400 |

Infectious agent antigen detection by immunoassay technique, (e.g., enzyme immunoassay [EIA], enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA], immunochemiluminometric assay [IMCA]) qualitative or semiquantitative, multiple-step method; Influenza, A or B, each |

|

|

87501 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); influenza virus, includes reverse transcription, when performed, and amplified probe technique, each type or subtype |

|

|

87502 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); influenza virus, for multiple types or sub-types, includes multiplex reverse transcription, when performed, and multiplex amplified probe technique, first 2 types or sub-types |

|

|

87503 |

Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid (DNA or RNA); influenza virus, for multiple types or sub-types, includes multiplex reverse transcription, when performed, and multiplex amplified probe technique, each additional influenza virus type or sub-type beyond 2 (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) |

|

|

87804 |

Infectious agent antigen detection by immunoassay with direct optical observation; Influenza |

| ICD-10 | R05.1 | Acute cough |

| R05.2 | Subacute cough | |

| R05.3 | Chronic cough | |

| R05.4 | Cough syncope | |

| R05.8 | Other specified cough | |

| R05.9 | Cough, unspecified |

Procedure and diagnosis codes on Medical Policy documents are included only as a general reference tool for each policy. They may not be all-inclusive.

This medical policy was developed through consideration of peer-reviewed medical literature generally recognized by the relevant medical community, U.S. FDA approval status, nationally accepted standards of medical practice and accepted standards of medical practice in this community, and other nonaffiliated technology evaluation centers, reference to federal regulations, other plan medical policies and accredited national guidelines.

"Current Procedural Terminology © American Medical Association. All Rights Reserved"

History From 2016 Forward

| 10/13/2025 | Annual review, updating CC1, signs and symptoms, and adding note 2. Also updating backgorund, rationale, and references. Removing CPT code 87631. |

| 10/07/2024 | Annual review, no change to policy intent. Updating table of terminology, rationale, references and reorganizing coding. |

| 10/24/2023 | Annual review, no change to policy intent. Entire policy updated for clarity and consistency.) |

| 10/21/2022 | Annual review, no change to policy intent. Policy verbiage reformatted for clarity. Updating table of terminology, rationale, references. |

| 10/08/2021 |

Annual review, no change to policy intent. Updating background, rationale, references and ICD 10 coding. |

| 10/01/2020 |

Annual review, no change to policy intent. Updating description, coding, rationale and references. |

| 10/10/2019 |

Annual review, no change to policy intent. |

| 11/15/2018 |

Annual review, policy being revised to encompass more than Rapid Flu testing. Updating title, policy verbiage and coding. |

| 10/30/2017 |

Updated Coding section. No other changes. |

| 09/28/2017 |

Updated coding section with 2018 coding. No other changes. |

| 06/19/2017 |

Updating coding section. No other changes made. |

| 04/26/2017 |

Updated category to Laboratory. No other changes. |

| 03/07/2017 |

Updated coding section. |

| 01/03/2017 |

Annual review, no change to policy intent. |

| 01/11/2016 |

NEW POLICY |